|

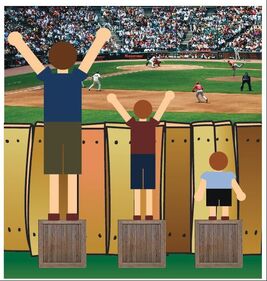

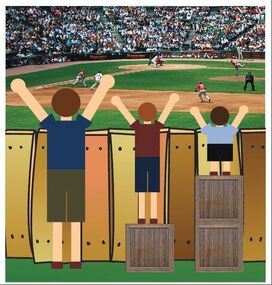

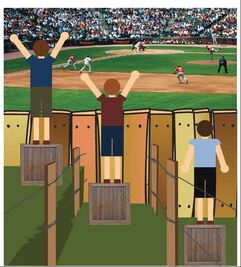

The killing of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement have sparked protests around the world and made the term “systemic racism” go mainstream. From reporters at major news outlets to the leaders of large corporations and non-profits, everyone is making proclamations against system racism and vowing to eradicate it. Yet, while many in high-profile positions claim to know what systemic racism is, they fail to understand that the solutions, too, must be systemic. Being nicer to each other does not change the policies and practices that keep Black people from being hired. Hiring more racialized police officers does not change policing practices that target Black and Indigenous people. Being more inclusive at the leadership table also won’t automatically change policies that fail to test for COVID-19 in the hardest-hit parts of the city. Systemic racism means that we can all be nicer to each other, hire people from diverse backgrounds, and create more inclusive workplaces and simultaneously reproduce racial inequality within organizations and society. Duke University sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva calls this phenomenon “racism without racists,” whereby systemic racism persists within organizations without overt displays of racially discriminatory behaviour from employees themselves. Racial inequality can be reproduced by nice people who effectively implement organizational policies that are racist. The pictures of the boys on boxes can help us explore this issue further. We’ve all seen the pictures, the one where the picture on the left represents equality and the one on the right represents equity. The pictures were designed by Craig Froehle in 2012 to illustrate a point he was making in an argument with a conservative activist. In his blog post chronicling the history of his illustration, Froehle says he created the picture to illustrate the difference between equal opportunity and equality of outcomes (i.e., fairness or equity). Using some stock photos and clip art, he put together the two pictures in about a half-hour and then posted them on Google+. The first frame of the picture shows that treating everyone the same may not result in equal outcomes. And, in fact, treating everyone the same can only work if everyone needs the same thing. The second frame of the picture depicts “equity.” Each boy has the number of boxes he needs to see the baseball game. The tallest boy doesn’t get a box because he doesn’t need one. His box has been given to the shortest boy, who can now see the game. When used in training, this image helps participants recognize that accommodation may be needed in the form of policy changes or providing an employee with specialized equipment to help them do their job. They see the boxes as representing these policy changes or accommodations and the boys as representing groups of employees rather than individuals. However, the second picture has one significant drawback — the gaze of the observer remains on the boys themselves. The conversation centres on the shortest boy and his deficiencies, which society must accommodate if this boy is to see the baseball game. As such, the solution to the boy’s shortness is to give him a box. Take education as an example. If the implication is that the shortest boy needs additional educational resources because of a deficit inherent to him, his family, or his community, society is saying that the shortest boy is less academically capable or comes from a culture that does not value education. The assumption is that there is nothing inherently wrong with a system that produces unequal educational outcomes. Even when the system produces inequality generation after generation, society continues to focus on the flaws “inherent” in individuals and communities, not the broken system itself. However, the more one reflects on this picture, the more one is prompted to ask questions like:

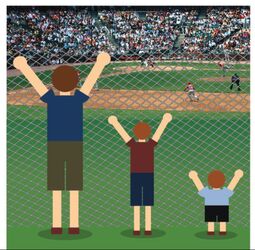

Broadening the discussion to the fence, which is often overlooked when discussing the picture. Changing our gaze from the boys to the fence helps us ask different questions: What is the purpose of the fence? Could a different type of fence serve the same purpose? Who designed and built the fence? Who benefits from it? Who is most familiar with the fence? Discussing systems rather than people allows us to look for other solutions — systemic solutions — such as a chain-linked fence. This type of solution does not require individual accommodation, but it does allow all the boys to see the baseball game regardless of their height.  But in reality, the boys don’t start with a level playing field. Even the picture with the chain-linked fence limits the conversation, and the question "Why can't the boys watch the baseball game from the stands?" is asked. We must instead shift to talking about structural racism and the social conditions that put these boys outside of the stadium itself. Structural racism “encompasses the entire system of white supremacy, diffused and infused in all aspects of society, including our history, culture, politics, economics and our entire social fabric” (Lawrence & Kelecher, 2004). Rather than simply looking at the policies and practices within an organization that produce and maintain racial inequality, we need to look at the social structures that work together to maintain racial inequality. These include the news media, entertainment media, cultural institutions, educational institutions, labour market, health care, child welfare, policing, and the criminal justice system. All these social structures build on the historical legacy of racism on which Canada was founded and that is embedded within our present-day policies and institutions.

This approach requires that organizations get used to holding uncomfortable conversations about systemic racism and to engaging in still deeper conversations about structural racism. We can’t talk about policing without discussing how the mental health system has failed Canadians, in particular racialized people. We can’t talk about poor outcomes for Black students in the education system without discussing the role of police both in public schools and on the campuses of our post-secondary institutions. We can’t talk about the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people in the child welfare system without talking about how the health care and education systems over-report them to child welfare, as well as addressing how society maintains Black and Indigenous people in poverty, uses issues of poverty to apprehend children, and then pays White families to foster these children. These are complex and interrelated issues that leaders of all institutions must grapple with. If they are struggling to discuss and understand systemic racism, they need to buckle up for much deeper conversations.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

TANA TURNERTana Turner is Principal of Turner Consulting Group Inc. She has over 30+ years of experience in the area of equity, diversity and inclusion. Categories

All

|